Engineering Marinas with Nature

Published on November 9, 2023As our waterfronts continue to face mounting development pressure across the country, it seems that all the “easy” sites to build a marina already have one and all we’re left with are the challenging sites. Challenging sites include those that have environmentally sensitive habitats along the shoreline such as wetlands, sea grass, or mangroves, or those sites that are exposed to wave climates and storm conditions that require more significant breakwater structures. Other challenging sites include natural sediment flows and littoral drift that brings sand or sediments into marinas creating the need for annual maintenance dredging. All these conditions increase costs and delay permitting, especially when a site includes all the above.

So, what is the developer of a new marina or owner of an existing marina to do when faced with ever increasing environmental regulations and costs? We are finding great success in the evolving field known as “Engineering With Nature®,” which as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers defines it “is the intentional alignment of natural and engineering processes to efficiently and sustainably deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits through collaboration.”

Living Shorelines

The Engineering With Nature approach to marina design includes very specific strategies that focus on “living shorelines” in place of armored and hardened shorelines; segmented habitat islands that create habitat while directing sediments where we want them to go, improve basin circulation and water quality, and provide protection from storms in place of traditional continuous structures; and expand access to the water for the broader community in addition to boaters.

A ”living shoreline” focuses on preserving or restoring the natural edges and geometries where water meets land. These are naturally very diverse ecosystems that also have landforms that are effective at absorbing or redirecting wave energy and minimizing wave reflection. They also provide benefit through “biofiltration.” Living shorelines are a band of planting between the shoreline, upland areas and parking lots, which removes pollutants and absorbs fertilizer from runoff before it enters the water.

This improves water quality and reduces the growth of weeds in a marina, reducing maintenance costs and boater frustration with weeds fouling their props and intakes. Gangways and floating docks or fixed docks can easily cross living shorelines to provide access to the marina, which will have a more beautiful edge, more wildlife, cleaner water, and calmer water.

Segmented Habitat Islands

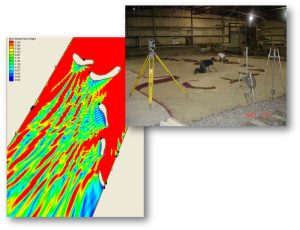

“Segmented Habitat Islands” is an innovative approach to providing wave attenuation for marinas and harbors that are replacing traditional continuous breakwaters in environments as varied as Florida’s intracoastal waterway, the Laguna Madre in South Padre Island, Texas, and the shores of Lake Michigan at Illinois Beach State Park. Advanced coastal engineering strategies combined with computer numeric “desktop modeling”, which is further refined through physical modeling in large scale wave tanks, have proven that we can design structures that are effective at creating an appropriate wave climate for a marina basin. We can even finesse sediment to move in different ways to minimize dredging and better preserve the shoreline, all while facilitating improved water circulation and better ways for protected fish species to move through the marina basin. Additionally, we can design these habitat islands with protruding fingers of stone that both trip the waves before they hit the island itself, meaning we can use less stone and lower breakwater elevations, while also creating “fish alleys” where fish can spawn, and juvenile fish can mature in more protected areas from predators. In some cases, smaller stone can be used, which reduces the risk to protected sea turtles from being trapped in the gaps between larger armor stone. The profile of the stone size can also be changed in different areas and transition through a series of different habitat zones that can support oysters at one level, mangroves at another, and dune grass and bird species at the top.

An excellent example of this approach can be found at Fort Pierce City Marina in Florida, where the facility suffered continuous sedimentation issues and was later destroyed by a hurricane. Working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), USACE, and Florida environmental regulators, the design team developed a strategy incorporating segmented habitat islands that achieved everything described above. Perhaps most important to the local community, this innovative project earned funding support from FEMA to the tune of approximately $18 million of the $20 million cost due to the highly innovative nature and effectiveness of the design in preventing future loss to storms. This clearly demonstrates that a project of this nature, while potentially more expensive than traditional approaches, can ultimately be much less expensive to the owner because grant funding agencies want to support habitat, reduce environmental impact from annual maintenance dredging, and of course potential catastrophic losses from storm damage.

Advanced coastal engineering strategies combined with numeric “desktop modeling” allows engineers the ability to design effective structures.

Securing Funding

The next logical step in securing grant funding for marinas through these innovative approaches is utilizing these strategies to expand public access to the waterfront for the local community beyond our traditional boating customers. As we all know, outside of the highly sought after Boating Infrastructure Grants and Clean Vessel Act grants from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and individual state waterways grants, there are very few other grant programs that will support private marinas. However, the South Padre Island Economic Development Corporation, City of South Padre Island, and Cameron County are taking a different approach by pursuing a public private partnership. The local governmental agencies collaborate with state and federal granting agencies to build a safe harbor using the strategies outlined above, and the private sector will build and operate the marina within the public harbor.

This approach has been successful all over the country, and in particular on the Great Lakes. So why would the state and federal agencies help fund the construction of what we’re calling the South Padre Island Marine Park? Because it is actually going to be a public park for everyone to use through low-cost access strategies including paddlecraft rentals, boat clubs, and public fishing piers. It will also protect the existing sea grass and mangroves, slow boats that are likely to encounter migrating sea turtles, and protect the shoreline from violent wind and waves driven by hurricanes. This approach aligns with the Texas Coastal Resiliency Master Plan, and the project has already been awarded USFWS Boating Infrastructure Grant Tier One funding to support the ongoing preliminary engineering and permitting efforts that are currently underway. When complete, the new marina will support approximately 5,500 linear feet of flexible broadside mooring intended to support everything from 90’+ sport fishing boats attending international fishing tournaments to smaller local vessels, shallow draft fishing boats, and even visiting superyachts. At the same time, the facility will create the first dedicated access and low cost paddlecraft rentals, which nearly anyone in the community can afford, to explore a marine park dedicated to improving and expanding habitat for dozens of species.

The key to the success of these projects is that they serve a much broader community than just the boaters. Challenging sites require a much more thoughtful approach to protecting the environment, expanding or restoring lost habitat, avoiding impacts, and expanding public access in order to be permitted at the state and federal levels. Equally important, expanding service to those without access to boats is a great way to build community support at the local level. All of these efforts lead to greater access to grant funding that would otherwise not be available to a private marina owner. Finally, embracing an engineering with nature approach simply results in more beautiful marinas, and many boaters want to have their boats in a marina where they know the facility is doing its best to improve the waterways and reduce its environmental impact. This leads to greater occupancy, higher rates, and more success for the marina owner. This exemplifies doing well by doing the right thing, and we expect to see more and more facilities embrace this approach in the coming years.

Editor’s Note: More extensive information on this topic can be found at the Engineering With Nature website https://ewn.erdc.dren.mil/.

| Categories | |

| Tags |