Successfully Navigating the Regulatory Sea

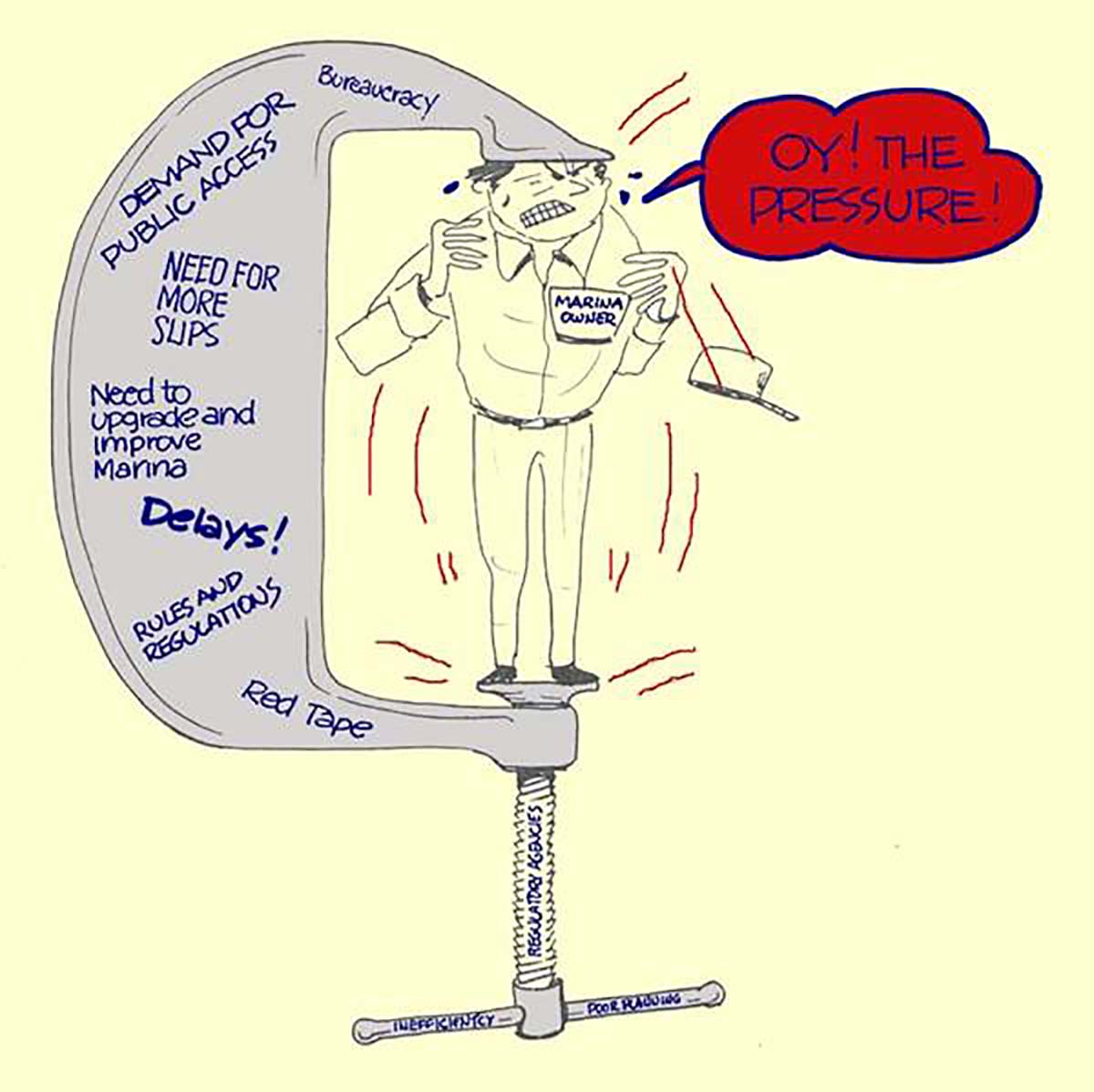

Published on August 31, 2021In today’s environment, the pandemic notwithstanding, you need a permit to do most anything. In most cases it is not one permit, but a virtual sea of permits typically from about every level of government – local, regional, and/or national.

As you may have heard me say before, whenever a new marina owner asks me what his or her ‘as-of-rights’ are, my not so facetious answer is, “the right to grovel.”

The regulatory burdens continue to become increasingly onerous, time consuming, and expensive to deal with. Then in addition to the promulgated regulations, there are also those in the agencies who have their own ideas as to how the regulations should be interpreted, or what they personally feel should be done, or what their bosses are requiring.

On the other hand, the genesis of most regulations has to do with seeking to do the right thing. But often the path from intent to outcome gets lost in the bureaucratic fog along the way, and sometimes that fog can seem as thick as pea soup! The problem is that most of those who write, review and/or enforce the regulations have never worked in the world of constructing, operating, or owning a marine related business.

The lack of ‘real world experience’ in the regulatory community presents a challenge to those seeking to improve their operations. The good news is that it is not an insurmountable challenge.

As one who has been involved in dealing with and being successful in meeting these challenges, I find that there are some common elements as to how to approach a project and steer it through what can seem like uncharted waters.

The three most fundamental of these elements would have to be: doing one’s homework; appreciating and addressing the intent of the various regulations; and providing full disclosure to the agencies. After that one might add talking with the neighbors and trying to address their concerns.

The Neighbors

Many would prefer not to talk with the neighbors or community organizations for fear of stirring up opposition. Our suggestion is that people react to many things, but how one finds out about something can be a major factor – especially if it is put in a bad light by one who is not happy about the project.

The rumor mill is rarely your friend. Neighbors will be notified as part of the application process. So, in most cases it is better to approach them directly, explain what is desired and how one will try to accomplish it, seek their input, and, if possible, try to mitigate any concerns. It is better to know what their objections will be prior to filing with the agencies so that they can be addressed as part of the application submissions.

Returning to the big three, doing one’s homework is essential to understanding the various issues, not only the physical issues one may face in design or construction, but also in assessing the various regulatory and legal requirements. Many think that a simple title survey may be sufficient, but it’s not. A meaningful topographical and hydrographic survey will be instrumental in undertaking meaningful designs as well as getting through the various regulatory hurdles. Other homework items might include looking at traffic impacts for expansion of facilities, borings for structural components, parking and accessibility requirements, pervious versus impervious areas, stormwater analysis as well as what happens to power washing water, how are hazardous materials handled, and any number of other environmental issues.

Fully understanding the various regulations, including whatever might be the current ‘cause du jour,’ is important to appreciate the regulators’ perspectives. And those perspectives often may differ from one agency to another, presenting yet more challenges in seeking to sail as smoothly as possible through the application process. Indeed, there are many regulator perspectives to various regulations, some promulgated and many not.

Understanding the perspectives can help determine how projects are presented. Addressing how the project meets the objectives of the regulations is most important. But it can also be meaningful to discuss how the project may not meet the intent of the regulations, why it cannot meet them, what has been done to mitigate the issues, what alternatives have been looked at and why they do not work, and what are the advantages of the project.

Part of the Team

We strongly recommend pre-application meetings. The approach is to try and have them part of your team by having a give and take dialogue. While the pandemic has made this much more difficult over the past 18 months, it is still important, even if it may have to be undertaken virtually as opposed to in the field. Providing sketches in advance with an outline of the project, and having the opportunity to explain it, helps create a mindset. It allows ‘unofficial’ feedback of their reactions in terms of what they may have concerns about and what they may think is desirable.

Pre-application discussions give an opportunity to have candid conversations about various aspects of the proposal and what other approaches might warrant consideration. This approach helps when the project arrives on their desk to undertake an official review, particularly if one can incorporate their suggestions or, if not, address why they may not be appropriate for your specific site or project. Agencies tend to be overly concerned about setting precedents that others might use to run a Mack truck through the regulations. So the more justification one can provide for your site-specific circumstances the better.

Regulators are human and appreciate being treated with respect. Do not lose one’s cool with them – that will not be helpful! And whatever you do, don’t lie to them. We are a big advocate for full disclosure, as there is nothing that will set you back more than losing the trust of those reviewing your project.

Successful Outcomes

Next, we have a couple of real-life examples where taking these kinds of tactics led to successful outcomes.

First, we had a client who purchased a coastal property where a sizable portion of the waterfront was mapped as a freshwater wetland. Due to its mapping as well as the regulatory protective buffer that it triggered, development approaches were significantly stifled. In our preliminary discussions with the town’s wetland agency and review of the regulatory criteria for such a designation, the mapping process was meant to be based on the area’s vegetation and soils. But the area in question was lawn grass with scattered specimen trees, which did not fit the definition of a freshwater wetland.

Knowing that the agency had never demapped a previously mapped wetland, we implemented the process in the regulation for investigation and designation. Three respected soil scientists from the town’s providers list were engaged to undertake joint investigations of the soil and then independent analyses and findings. Our client asked why three soil scientists were necessary. Our response was that it should be assumed the agency will start off with a negative mindset, and if one soil scientist is hired and finds it is not a wetland, then the agency will hire another from the same list, and if they do not agree, a third would be jointly agreed upon to make a finding. By hiring three from the get-go, if they all agree (which we suspected would be the case – and was), the agency would not likely question the findings. This aggressive move, pared with a very respectful approach to working with the agency, resulted in being able to move forward with the project. Yes, it meant spending more money upfront, but, in the end, that meant less time and money going through the entire process and achieving a successful outcome.

In another situation the marina occupied a curving section of waterfront along a tidal river, with about half the waterfront long ago developed with mains and fingers, and the rest with the upland bordered by saltmarsh, mudflat, and eventually the Federal Navigation Channel. The marina was desirous of expanding but believed it would not be possible due to the environmental constraints. The client agreed to undertake an in-depth hydrographic and topographical survey of the entire area, including mapping the voids within the marsh grasses, the edge of the mudflat and the location of the Federal Channel, as well as the previously developed upland shoreline area. Armed with the detailed survey information during an onsite pre-application meeting, we discussed the idea of placing a curved main and series of branched fingers forming a sort of semi-circle waterside of the sensitive environmental resources and landside of the Federal Channel. There would be a connection to the main marina as well as a fixed access pier high above the top of the marsh grasses and following as much as possible the voids between the grasses, thereby minimizing any shading impact. The approach would meet the various environmental criteria as well as foster the Coastal Zone Management provisions to enhance and foster recreational boating access to the waters. The agencies went from concerned to supportive as the environmentally sensitive resources would be protected and boating access would be enhanced – a win-win for the environment, regulatory overview, the development desires, and additional access by the public.

In a third situation a marina only had one area that could be developed to expand in-water berthing to meet the increasing public demand. The problem was it was adjacent to a healthy saltmarsh and did not have adequate water at low tides for boat berthing. The owner had been told that the agencies would never approve any dredging or expansion in that area due to the potential undermining and compromising of the marsh. Working with the agencies we suggested a subaqueous bulkhead along the edge of the marsh that would have its top below water at high tides, allowing the marsh to be continually flooded with the tidal waters (a major requirement), while also allowing dredging and the installation of more docking facilities without destabilizing the marsh. It was a novel concept, and the agencies took some convincing. But with multiple field visits, hydrographic surveys of the subject area, and related work, together with the demand for public access (a significant federal, state, and local coastal management policy), the agencies agreed to a demonstration project (so that it would not set a precedent), and permits were issued. The marsh not only was not disturbed but became even healthier – and more of the public gained access to the water. It is now used as an example of how one can be environmentally enhancing while allowing for in-water development.

Getting it Accomplished

Understanding and working with the regulatory agencies can be meaningful and successful. Not that there will not be times when the seas get choppy and the agencies a bit difficult. But having a constructive and open to compromise approach can make a significant difference. If one has done their homework, then as suggestions are made the various cause and effect issues can be discussed – including why they may or may not work – or how they might be able to be tweaked to be incorporated into the project. You might even find that you don’t need to grovel!

Happy navigating

Dan Natchez is president of DANIEL S. NATCHEZ and ASSOCIATES Inc., a leading international environmental waterfront design consulting company specializing in the design of marinas and marina resorts throughout the world. He invites your comments and inquiries by phone at 914/698-5678, by fax at 914/698-7321, or by email at dan.n@dsnainc.com.

| Categories | |

| Tags |