Emerging Approaches for Building Aquatic Habitat into Harbor Infrastructure

Published on June 28, 2019

Harbors are often thought of as

habitat deserts. While common edge treatments such as concrete seawalls and steel sheet pile are effective in many ways, they offer little in terms of shelter or benefit for aquatic life.

This dynamic is changing, however, with the growing emphasis on environmental protection and mitigation in harbor construction and renovation. Professionals charged with managing, regulating and designing waterfront facilities are increasingly looking for answers to an additional set of questions.

How can harbors better integrate habitat that benefits aquatic life? And how can this be done in a way that improves human habitat by enhancing the visitor’s experience of place and connection with nature? A great deal of experimentation, prototyping and innovation are leading to new approaches for enhancing biodiversity within recreational and commercial harbors.

The Biophilic Marina

Designing for improved human connection to nature is a core philosophy behind biophilia – a growing trend in urban and architectural design. Cities throughout the world are looking at how the natural and built environment can co-exist as a higher performing ecosystem. As Tim Beatley described it in a 2014 interview about his book Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, “The biophilic city must be resilient and sustainable, but biophilic design ought to put people in close contact with nature as it is part of our very being, our innate need to connect with nature.”

The concept has growing ethical and economic relevance for marinas and harbors as the requirements for addressing environmental impacts increases. Mitigation along the West Coast is now required as a result of soft-bottom habitat losses; within facilities such as Los Angeles County’s Marina del Rey, ongoing maintenance to halt undermining of seawalls within the harbor must effectively balance financial and ecological considerations.

Along the St. Mary’s River in Georgia, concerns over low oxygenation levels and water quality within a proposed marina basin have slowed project development to better protect manatee breeding grounds.

In Puget Sound, development of a floating harbor for a tribal fishing fleet has met with extensive review related to eel grass bed protection, and high mitigation requirements due to dock shading and the potential for anchor-chain whiplash effects on vegetation.

Regardless of geography, these regulatory requirements can be expected to increase, along with the understanding that making harbors more habitat friendly can also make them more appealing to users and visitors.

A good example of a biophilic habitat-improvement approach to shoreline protection design can be seen at Caesar Creek State Park Marina in Ohio. Extensive fish spawning beds replace and enhance traditional shoreline revetments. The approach enhances the park and marina’s natural aesthetics, while supporting the sportfishing, which helps make the marina a regional destination.

The New Norm

While the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has traditionally emphasized operational efficiency and hard engineering of coastal infrastructure, they are becoming increasingly aware of the need to integrate softer, nature-centered solutions. The relatively recent adoption of Nationwide Permit 54, which supports development of living shorelines in certain conditions, and the Corps’ growing national investment in river habitat restoration are indicators this isn’t just a fad. Starting around 2012, the Corps created a new pilot program dubbed “Engineering with Nature.” It completed its first Great Lakes project in Cleveland, using special concrete molds to create heavily textured and grooved 10-ton armor units as part of a breakwater repair project. The surface undulations and grooves provide needed habitat for benthic macroinvertebrates and algae, critical species near the base of the aquatic food web.

The Corps isn’t alone getting into the habitat-creation game. Consultants, vendors and companies are all capitalizing on this increased environmental regulation and awareness, and the desire for improved harmony with nature. Companies such as E-Concrete are developing different types of pre-cast, habitat-enhancing armor stones for integration into breakwater structures. Their products were showcased in the award-winning Living Breakwaters project for Staten Island. Part of the Rebuild by Design competition following Hurricane Sandy, these offshore coastal-defense structures integrate oyster reefs, E-Concrete’s pre-cast armor stones, and other elements. Although covering up portions of the native seafloor, they create new habitat that supports species diversity while enhancing community resilience.

The Next (Re)Generation

As the examples above show, modifications to core infrastructure represent the next generation of harbor habitat creation. Dr. John Jannsen, fisheries biologist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, offers an interesting perspective on the potential for creating productive unnatural habitat within harbors. While tracking species found within Milwaukee Harbor, he and his graduate students identified what he describes as some “pretty unusual habitats.” Fish and other species were using derelict spaces and historic infrastructure designed for completely different purposes as habitat: areas of the harbor that had essentially been forgotten and left to grow “wild.”

Dr. Jannsen refers to these areas as feral landscapes and contends that the habitat value from a fish’s perspective is often the same, when compared with a more natural restoration. His research indicates that these unintended manmade habitats play a critical role in harbors – and that their ecological benefits can be intentionally replicated. The large-scale retrofit of the Seattle’s Waterfront seawall infrastructure is a good example of intentionally realizing these benefits. The design integrates shallow shelves, alternative walking surfaces that allow for improved solar transmission into the water, and heavily textured surfaces to support the benthic growth and informal habitat along the seawall.

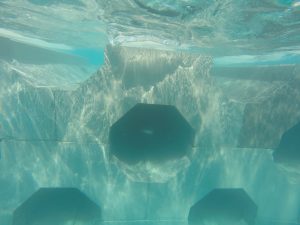

Even Volvo, the company known for producing one of the safest cars on the road, is diving into this pool. As part of its Ocean Conservation Project, the company partnered with the Sydney Institute of Marine Science and Reef Design Lab to create the Living Seawall in Sydney, Australia. Made with recycled plastic, the hexagonal-shaped, 50-tile installation applied to the existing seawall mimics the web-like root structure of native mangroves. It is intended to support colonization by filter-feeding organisms that can absorb and filter pollutants in Sydney Harbor.

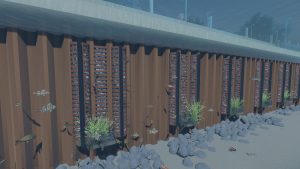

This kind of product innovation and prototyping continues to expand. Textural variation in substrates and other materials has long been recognized as beneficial to aquatic life. E-Concrete has expanded its line of textured products to include a new line known as the ECO Seawall. These heavily textured pre-cast panels can be attached to existing seawalls to enhance habitat and biological diversity. Monitoring of these systems shows them serving as habitat not only for invertebrates, including sponges, oysters, bivalves, bryozoans and coralline algae, but also for larger marine life.

City Dock in West Palm Beach, Florida, integrates oyster beds and aquatic plantings in specially designed perforated tubs that hang in the center of the dock. Not only do these elements offer habitat and contribute toward water purification, but benches and lighting have made these features a huge hit with the public, too. The Habitat Hotels, developed through a collaboration between the Milwaukee Harbor District and local higher education institutions/researchers, essentially act like underwater birdhouses for aquatic life; they are designed to be installed along sheet pile walls. The floating habitat island prototypes being piloted in Baltimore Harbor represent another potential method for reestablishing habitat in an environment dominated by hard infrastructure.

Waterfront communities throughout the world continue to look for ways to improve ecological performance and benefits, and regulations continue to demand it. While larger-scale environmental restoration efforts remain a critical part of the overall response, there are also new options and emerging opportunities to improve habitat as part of a harbor area’s built systems and infrastructure. Doing so isn’t just in the best interest of our aquatic friends. It’s important for people, too, as it deepens their connection with nature and makes marinas and harbors more appealing and attractive destinations.

Jason Stangland is SmithGroup’s Waterfront Practice Director. He can be contacted at 608-327-4412 or at Jason.Stangland@smithgroup.com

| Categories | |

| Tags |